Notes from the rural & village experience

One of the most life-changing and meaningful parts of the entire two-week elective are the days and nights we spend in Punjab’s rural countryside, learning from social and political activists among the backdrop of India’s poorest and most disenfranchised villages. And to date, no one has described the experience – which at times does seem indescribable – as well as Dr. Meghann Fitzgerald has. She is a cardiac anesthesiologist and was this Fall’s faculty mentor. These excerpts are a bit longer than a typical post, but well-worth the read…

“In bed at 2am and out the door by 6! Well, maybe it was closer to 7. Our survival through the harrowing journey on two lane roads is a testament to the skill of our drivers. The pothole ridden two-lane roads have no dividers and are shared with horse drawn carts, scooters, motorcycles, buses and long-haul trucks. Everyone drives fast and passes each other with vigor. Sometimes cars pass the cars that are passing, and always in the face of oncoming traffic. We didn't see any accidents or injuries but you can definitely see how this driving leads to the high rates of traffic injury. Everyone dozed on the ride there. Sleeping was a better alternative to witnessing the driving and imagining your life could be over in an instant.

I opened my eyes just as we were turning into the driveway at Jaijee Uncle's house, which really should be called an estate. The tree lined driveway lead to the main house, then another driveway lead to the guest house where we would stay. Surrounding the house was 18 acres of land owned by JaiJee Uncle, the limit for any farmer in Punjab. Families increase acreage by holding land in the names of several different people in the family. The peaceful acreage surrounding the house was idyllic. Guava and nectarine trees, open land waiting to be seeded, and endless rice fields. Beautiful flowering trees and bushes of orange, blue, and white flowers with lucious green leaves. And a dense fog hung in the air giving everything a mystical and dreamlike quality, accentuated by the intoxicating aroma of jasmine. But it was so, so hot and there was no breeze.

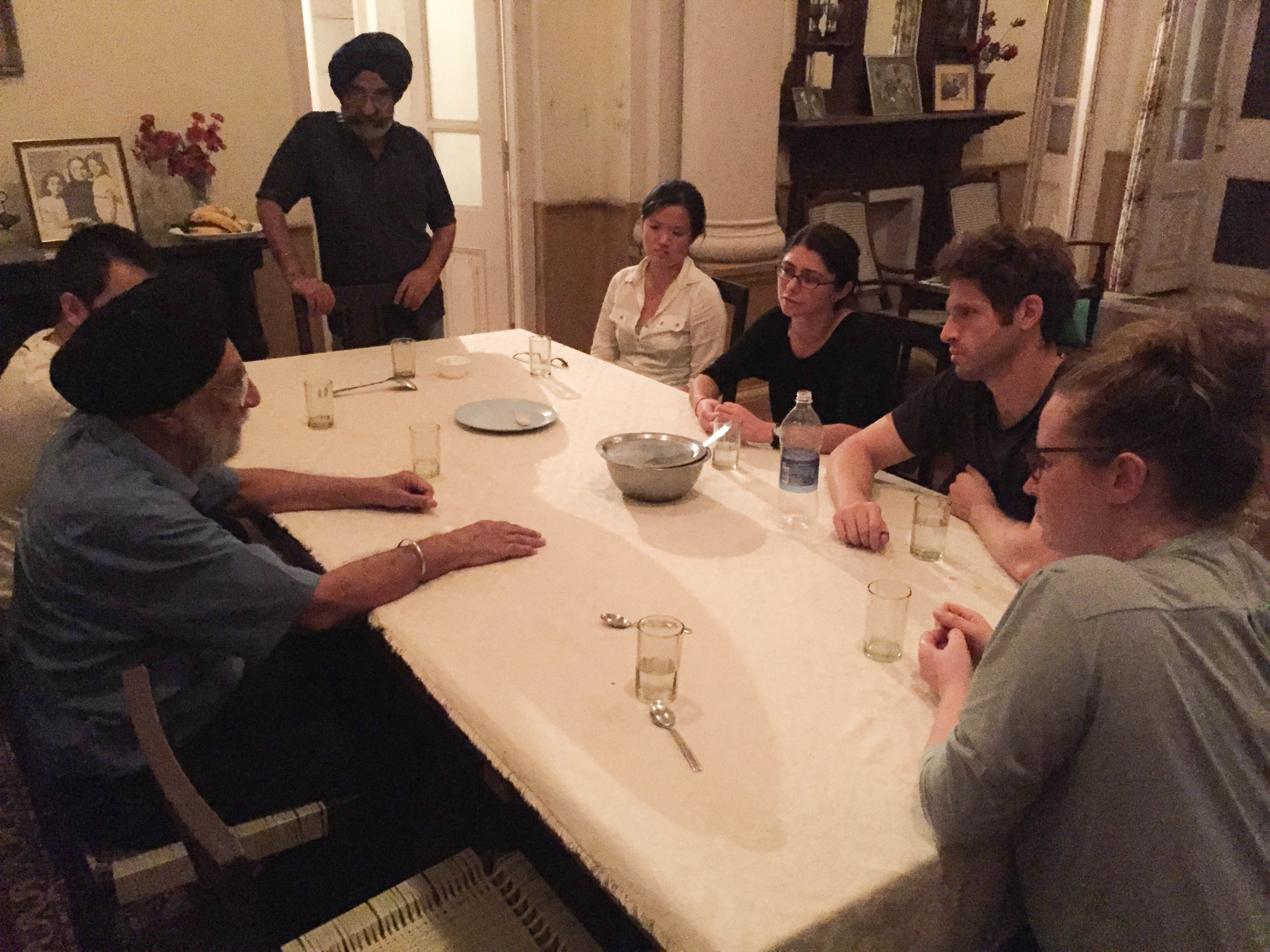

We were greeted by the men who work for JaiJee Uncle, all politely nodding, hands together in front of the chest, saying 'Sri....' JaiJee Uncle came to meet us, a tall Sikh with a slight tremor and a calming presence. We sat and chatted about our plans in the village. JaiJee Uncle is doing what he can to help his countrymen because he has seen, up close, the impact that Indian economic and political policy of the last century has had on Punjab. He previously worked in finance and throughout his life has been a political activist. He is probably over 85 years old and instead of relaxing in his twilight years, he continues to be a leader in Human Rights and social activism. He personally meets, interviews and approves every family that his group adopts.

Our visit in the village started with a visit from a woman who heard Jaijee Uncle was there so travelled 30km to ask him for help. She and her mother-in-law hitched a ride on a scooter to get there. Unfortunately, they lived outside of the NGO's territory rendering them ineligible for assistance. It wouldn't be feasible to deliver aid and follow up with the families at such a distance away. Instead Jaijee Uncle opened his own wallet and gave them some money. He took them to a room with donated clothing and Gunisha helped them pick out some clothes for them and their sons. Though they had little themselves, they were particular about the clothes they accepted. Respectably they had pride in their appearance. About one dress that was several sizes too large for the mother-in-law, she said, 'what will people say if I wear this?”

We went to visit the sewing centers established to train women who otherwise would have been left to work in the fields. It is difficult for poor farmers to raise women due to the expectation she will give a dowry to her husband's family and be responsible for the wedding ceremony. By teaching them to sew, they can make clothes that will make their dowry and give them a useful skill other than relying on farming. The women were initially quite shy but probably just being polite. They showed us completed shirts and tunics though they’d just started learning two months prior. Before we left they asked us for a group photo; some asked our names and we exchanged pleasantries. When we left their excited chatter filled the air behind us. Of course we had to stop for cha with the men. We visited two other similar centers and at the last were able to buy some incomplete keychains (we couldn't wait until they were done!) and bracelets.

Our next visit was to the college established primarily be Jaijee Uncle's daughter and named after his brother who gave a large donation when it was built. It had the atmosphere of a typical college campus with some extra excitement due to the upcoming festival and competition with other local schools. They practiced their traditional folk dance and social commentary skits for us. They had so much energy and enthusiasm. Even though I couldn't understand the language, it was a pleasure to watch.

In the evening we went with Jaijee Uncle to visit families he would potentially adopt. We drove awhile to get to the first family; then somehow navigated tiny alleys and found the residence. The streets were lined with gutters that had litter and probably sewage floating through it, which the occasional pig or cow used as a feed trough. It's hard to tell how many family members lived in one residence but it was probably a lot. The homes had dirt floors, brick walls, limited electricity and probably only one water source. The father of the first family committed suicide (typically over an average farming debt of roughly $160) by ingesting pesticides a few months ago. The oldest son, previously a good student, found it too difficult to concentrate since his father died so had stopped going to school. He cried quietly when we spoke about him. The younger one continued to attend but with only one child in school, the family is ineligible for support from the NGO. Jaijee Uncle told the older son to get back in the fight. We visited two more families next. We discussed the circumstances of the family member's death, how much debt they had, and Jaijee Uncle signed off on adopted families. In each place the living conditions were startling. Yet they offered us cha and many smiled as they watched the Westerns pile in and out of cars. The next day we survived our trip back to Amritsar. We went shopping for gifts and for ourselves. It was hard to justify spending so much after witnessing the poverty we'd just seen. How am I going to go back to Manhattan and pay multiple more in monthly rent than many of the villagers will see in their lifetime?"

We'll have a final update on our experiences in India in a couple of days.

EB